After posting about Honey B’s trip recent trip to the clinic, many of you on the blog and social media had great questions. I thought we could take this opportunity to answer a few in greater detail here.

How do you isolate a chimp that needs treatment in the veterinary clinic?

The first step in bringing a chimp into the veterinary clinic for treatment is to isolate them. Each wing of the building contains a series of smaller rooms, which we refer to as “front rooms” due to their proximity to the human areas of the building. The front rooms may not look like the most desirable places for a chimp to spend their time but they are open to the chimps on a regular basis just like the playrooms and greenhouses and are actually quite popular spots for sleeping, monitoring the humans’ activity, watching television, or simply finding a quiet spot away from the rest of the group. They are generally smaller (most are approximately 8’W x 8’L x 10’H) and they have surfaces meant for easy cleaning and disinfection, as opposed to, say, the grass, mulch, and bamboo found in the greenhouses. One front room in each wing lacks the benches, ladders, food chutes, and other more permanent “furniture” found in the others, and these are the rooms where we isolate the chimps for anesthesia. The lack of furniture limits the potential for a chimp to fall as they succumb to the anesthetic, as some chimps may be inclined to climb up and perch if they are feeling sick or scared.

Cy likes to read magazines in the medical room (Front Room 7):

If a treatment or exam is planned in advance, we typically try to get the patient into one of these medical rooms the night before. This is done for two reasons: 1) so that we can begin early the next day, and 2) so that we can restrict their food and water intake. In the new wing, for example, each “lixit,” or water fountain, has its own shutoff so we can turn just their water off a couple hours before the procedure. Of course, some procedures are conducted on an emergency basis and we have no choice but to forego fasting.

Getting the patient into the medical room—and getting the others out!—is the part of the process that strikes fear into the hearts of caregivers everywhere, especially when outside professionals are coming to assist with the procedure (No pressure but the cardiologist will be here promptly at 7am and the dental surgeon has to get back to their practice by 10!). Though it can be a challenge, the staff have always been successful (eventually). It just takes a little patience and a lot of bribery. Honestly, sometimes the cattle are more difficult to sort than the chimps.

Ideally, we end up with the patient in the medical room with the other front rooms empty so that there is no peanut gallery to cause interference and we can safely enter adjoining rooms if necessary. We have found that, contrary to what one might think, there is no reason to restrict the rest of the group from seeing what is happening and in fact letting them observe from afar seems to help ease their concerns. Thus, they can often watch from a nearby window.

How do you get a chimp into the veterinary clinic?

Once the chimps are in the clinic they are usually maintained on a gas anesthetic, but they have to be immobilized before we can safely take them out of the front rooms in the first place. For this we use an injectable anesthetic. And there’s just no getting around it—this part usually stinks.

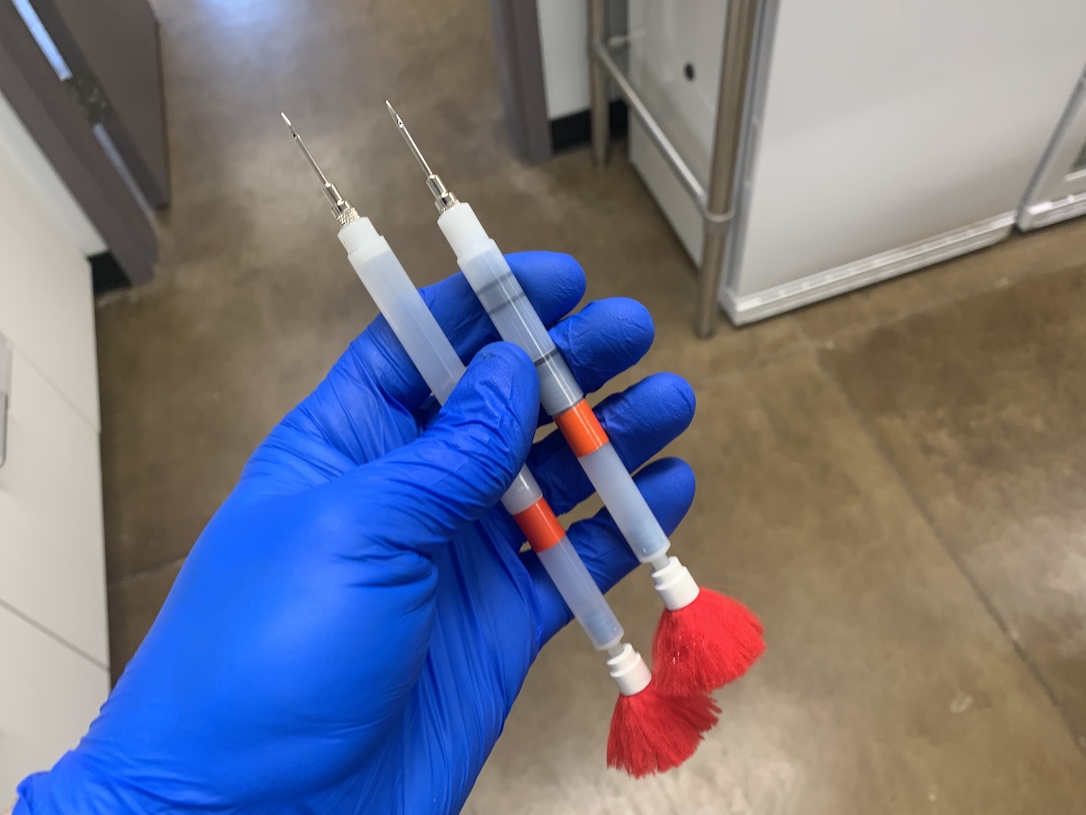

We often begin with an oral sedative or anesthetic to help reduce their fear and anxiety, and follow this sometime later with an injectable to fully anesthetize them. Many of the chimps have been trained, or in some cases maybe even learned on their own, to cooperate with the injection. Right off the bat this takes 90% of the stress out of the process. For the chimps that do cooperate, our Positive Reinforcement Team works to maintain that cooperation through routine practice with blunt or small-gauge needles—getting the chimps to present an arm or leg against the caging, poking them, and then rewarding them for their participation. For those who don’t, the team meets them wherever they are and works to increase their tolerance without provoking fear or anxiety. Will every chimp that spent decades in a lab getting poked and prodded against their will learn to cooperate? It’s theoretically possible but logistically improbable. Still, it’s a worthwhile goal.

When a chimp doesn’t present for the injection-by-hand, we have to fall back on other methods such as a pole syringe or the dart gun. Ideally, they have enough oral sedative or anesthetic on board that the trauma of the injection is short-lived and quickly forgotten.

Once they’ve been given the injection, we turn the lights down, remain quiet, and monitor them. If we got the full dose in, they are out within 10-15 minutes but sometimes they need to be “bumped up” before we enter the room. We have a number of tests to evaluate their plane of anesthesia so they we don’t get surprised by a seemingly immobilized chimp suddenly jumping off the cot on the way out the door. The staff lift the chimp into the stretcher, roll them onto a scale to quickly check their weight against the last measurement we had on them from the bench scales inside their enclosures, and then it’s off to the clinic, where a team is waiting to start the IV and gas anesthesia.

The staff monitor Honey B with the lights dimmed after her anesthetic induction:

What happens when the procedure is over?

As the procedure is nearing its end, the chimps are taken off the gas anesthetic, which will continue to have an effect, and wheeled back to their room, which in the meantime has been cleaned and set up with piles of blankets for comfort and space heater just outside the caging for extra warmth. Depending on which type of anesthetics they were given and how much, it can take them anywhere from minutes to hours to begin to sit up. During this time we pay close attention to their vitals and their airway since anesthesia continues to present serious risks until they are fully recovered. If the chimp only underwent an exam, they could theoretically rejoin their group as soon as that same evening, provided it is clear they could safely run and climb around the enclosures should the group get a little rowdy. But typically they will get a good night’s sleep and rejoin the group the next day. If the recovery is slow or the chimp underwent a major procedure, staff will either sleep at the chimp house or come up to check on the patient throughout the night, with many photos and status updates shared amongst the staff for peace of mind.

The staff monitor Honey B as she lays in a bed of blankets in the medical room just outside the clinic:

Are you interested in learning more about the veterinary care provided at Chimpanzee Sanctuary Northwest? Check out some of our veterinary blog archives.

Still have questions? Ask away and we’ll do our best to answer in the comments below.