Cardiovascular disease is a major cause of illness and mortality in captive chimpanzees. As many of you know, we’ve been treating Burrito since 2012 for hypertensive heart disease. What you may not know is that Cy also suffers from cardiovascular disease – in his case, dilated cardiomyopathy. To better manage his symptoms and slow the progression of the disease, Dr. Erin arranged for a cardiac exam from Dr. Lynne Nelson, lead cardiologist at Washington State University’s veterinary hospital. Dr. Nelson has been a great friend to the sanctuary for many years and has helped oversee Burrito’s care.

Dr. Nelson’s expertise was also called upon this week to assess Lucky. While Lucky has appeared to be in good health overall, her pre-transport exam from Wildlife Waystation suggested the possibility of an enlarged heart. We knew that further diagnostics would be required once she and her friends settled into their new home and social group.

And then there’s Terry. Terry has not shown any signs of cardiovascular disease, but he was due for a re-check of his fractured canine tooth, and any time a chimpanzee is anesthetized in the clinic, we want to obtain as much information as we can to help manage their care. Dr. Erin thoughtfully scheduled Terry’s re-check at a time when he could also receive a thorough evaluation from Dr. Nelson.

Three chimps in three days. Heart Week, you might call it. Or Hell Week, if you are a member of the staff responsible for getting the chimps into the right enclosures at the right times so that we could make this all work. We are incredibly grateful to all of the staff and volunteers for all the effort that went into making these exams possible while keeping the rest of the chimp house humming along like usual.

Before I share more of the week’s events, I’m sure you want to know what we found. Lucky has a healthy heart for her age, thankfully. Ultrasound revealed a few things that we’ll want to keep an eye on, but she does not suffer from any significant cardiovascular disease. Cy’s echocardiogram showed some improvements from his last exam—likely from the medications he has been on—but also some disease progression. Dr. Nelson was able to recommend changes to his medication regimen that should help. Terry’s exam showed good news on both fronts—his fractured tooth is healing nicely and his heart is healthy for his age, though he shows some mild cardiac changes that warrant monitoring every few years. Thankfully, he doesn’t have any signs of heart failure and requires no medication at this time.

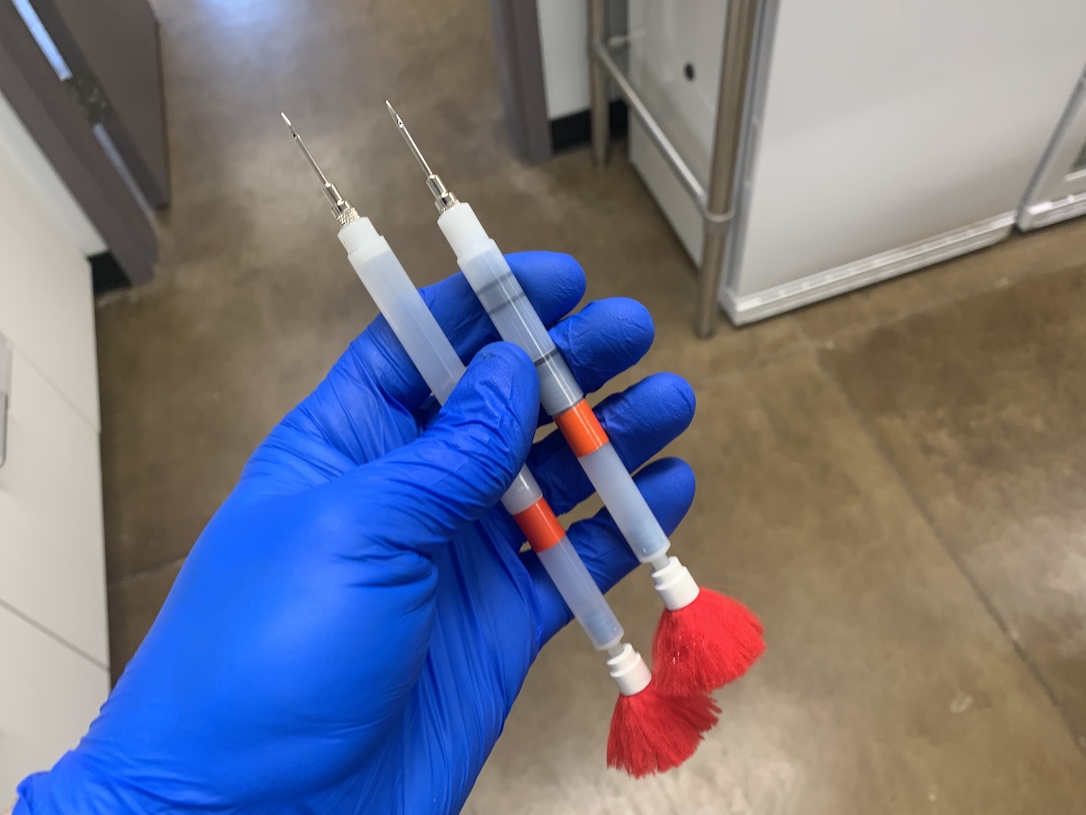

It’s not fun for us to have to bring the chimps into the clinic, but it is at times necessary. One of the ways that we can reduce the trauma associated with exams under anesthesia is to work with the chimps so that they will take an injection by hand, rather than by dart. Our positive reinforcement training team, and the work of others before us at the Waystation, made it so that all three chimps willingly presented their arms and legs for their anesthetic injections. According to Jenna, who has been training with Lucky, Lucky was downright nonchalant about being poked. The Valium-spiked sip of juice probably helped a little, too.

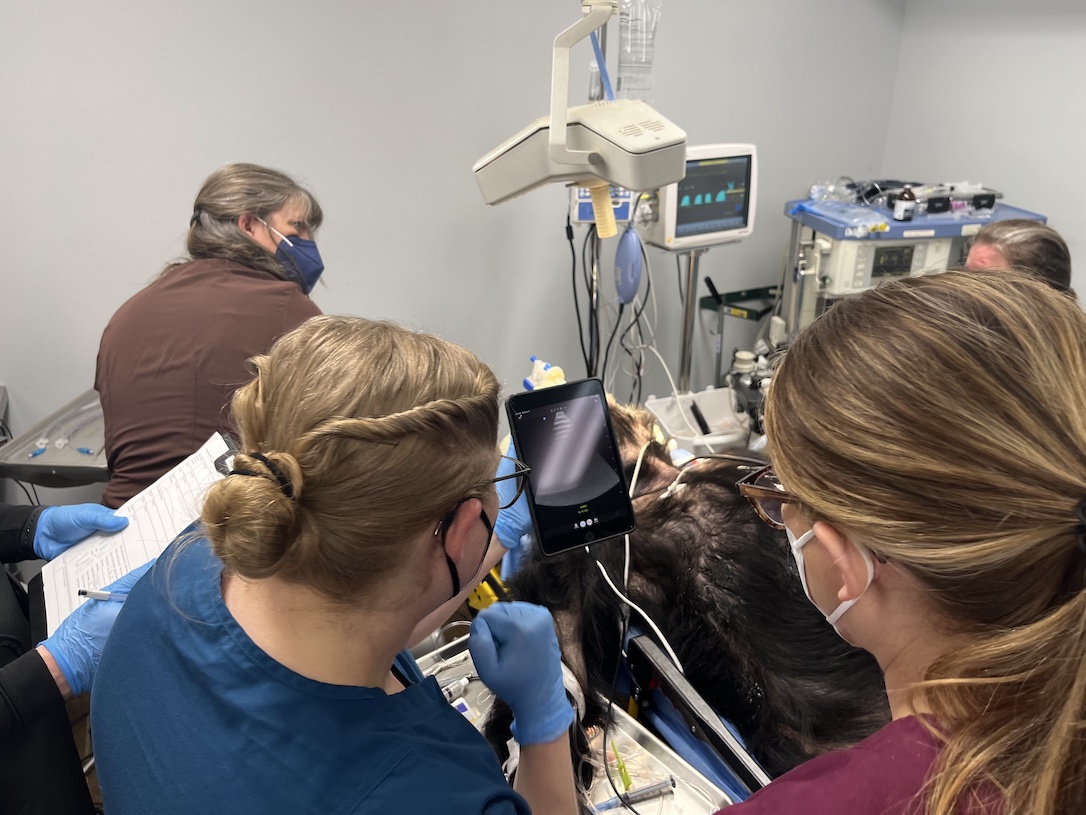

As is often the case here, Dr. Erin, Sofia, and Dr. Nelson were aided by a number of other medical professionals who came to volunteer their time and talents. Mekensie Kmack, CRNA, who has helped many times before, oversaw Lucky’s anesthesia. New to the team this time was Marneye Driesen, who assisted with the echocardiogram.

Some of our procedures, such as abdominal radiographs, are performed outside of the clinic while the chimps are in recovery (but still anesthetized) to minimize time under anesthesia.

It’s important to keep the chimps warm during recovery – these socks are not just for fashion.

The same team assembled again the next day to examine Cy’s heart and perform routine diagnostics and cleanings.

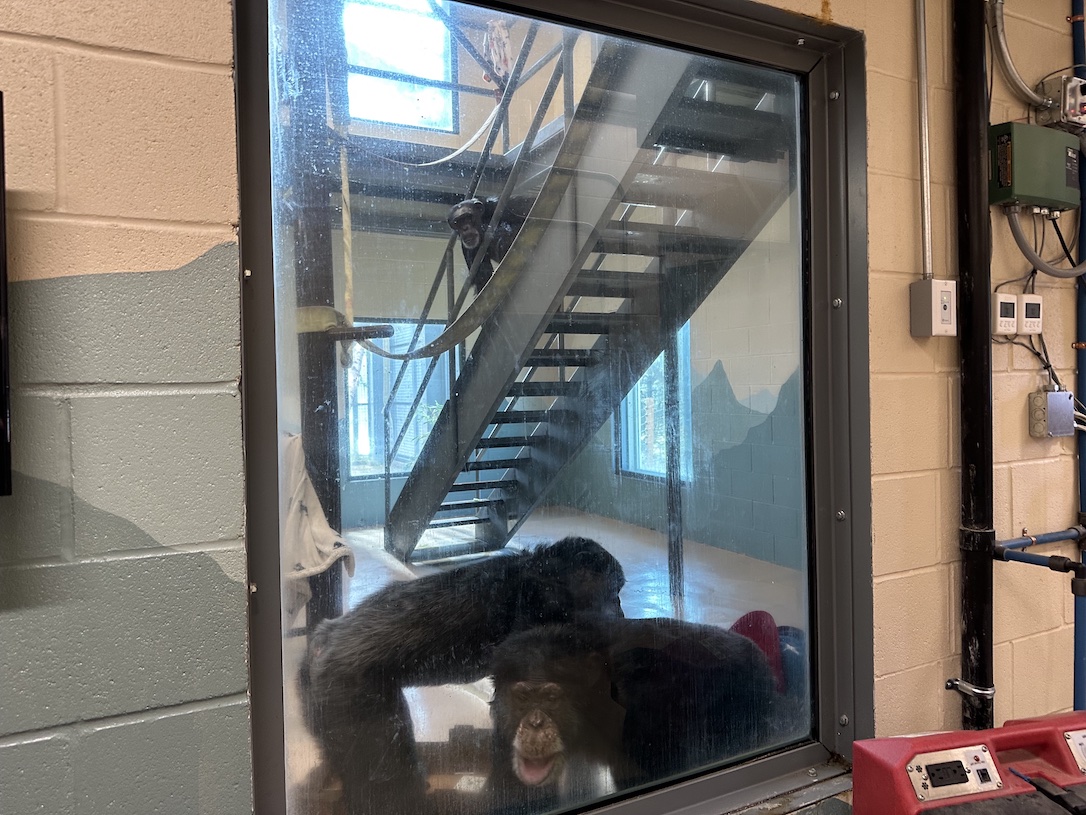

We’ve found that there’s no use hiding what is happening from the other chimps. Once someone is out of the clinic, they are laid in the recovery room while their friends look on through windows or neighboring enclosures. This reassures them and provides a comforting presence when the chimps wake up from anesthesia.

Cy was groggy, as is to be expected, but he perked right up as soon as Kelsi put on one of his favorite movies, Must Love Dogs.

It was unfortunate that Terry had to return to the clinic so soon after having his fractured tooth repaired, but it was important to get x-rays of the tooth and underlying bone to ensure that he had healed properly. Dr. Whitemarsh, DMD, was on hand again to help.

Sonographers Korey Krause and Tanya Herbert, also new to the team, performed an abdominal exam while Michelle DiMaggio, LVT, monitored anesthesia and otherwise assisted Dr. Erin.

As I write this, Lucky and Cy have been reunited with the group. Terry, who had his procedure this morning, will remain apart for the night while he recovers. Hopefully the others let him get some rest.

As usual, the information we collect to help the chimps in our care will also be shared with the Great Ape Heart Project, so that we can help other captive apes suffering from cardiovascular disease.

Many thanks to Dr. Erin, the staff, and the amazing team of medical professionals that came to care for Lucky, Cy, and Terry this week. Thanks as well to all of our donors that make this level of care possible. If you’re interested in the veterinary care we provide at Chimpanzee Sanctuary Northwest, why not register for our upcoming Virtual Visit on Saturday, April 15th at 2pm? To learn more, click here.