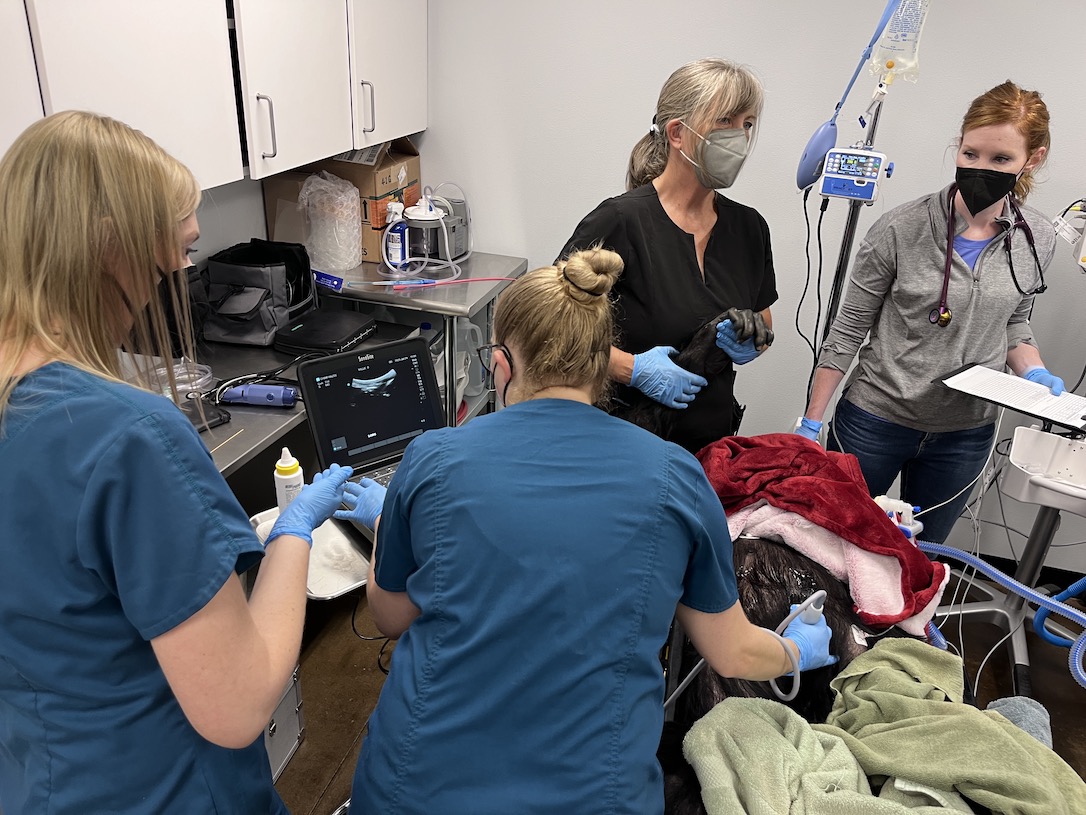

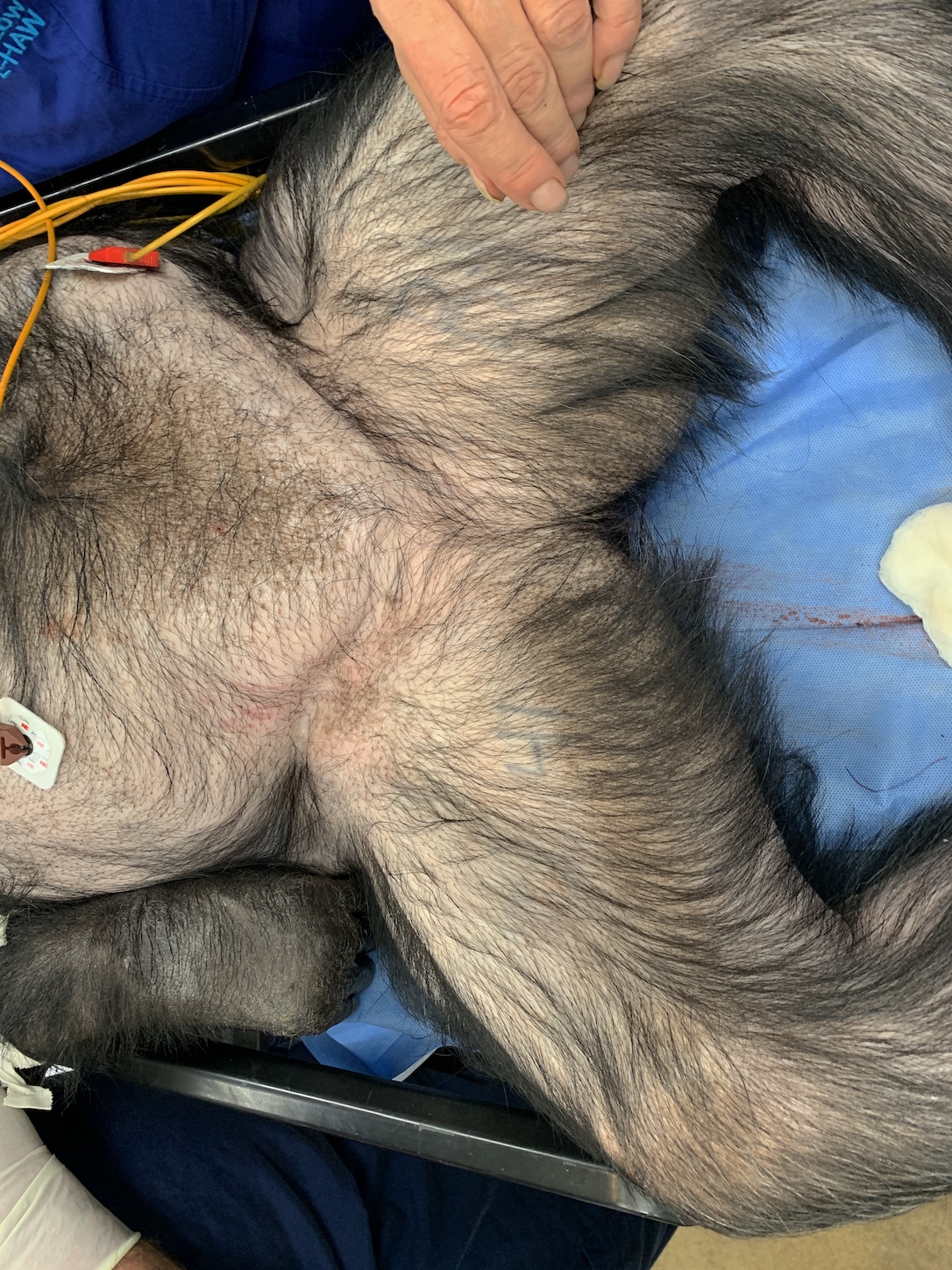

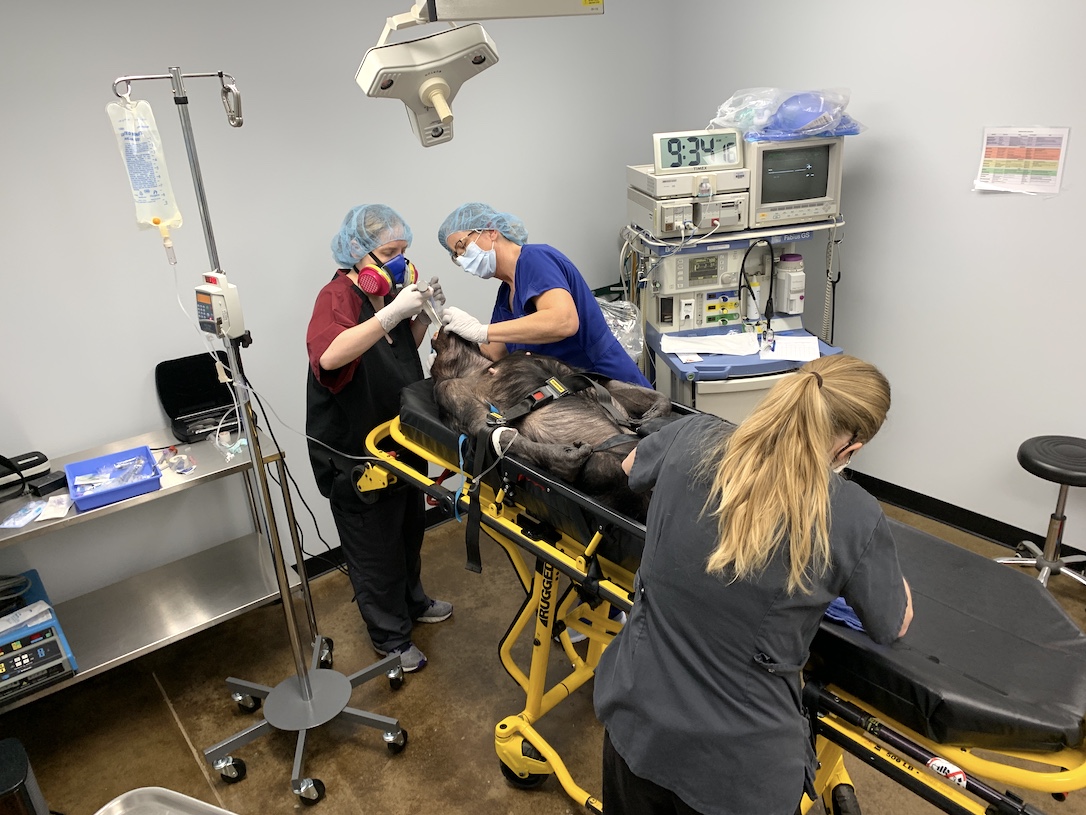

Willy B took a trip to the clinic this morning. The main purpose of the procedure was to investigate some swelling in his scrotum. As usual, Dr. Erin assembled a great crew to ensure that Willy would have the best care possible.

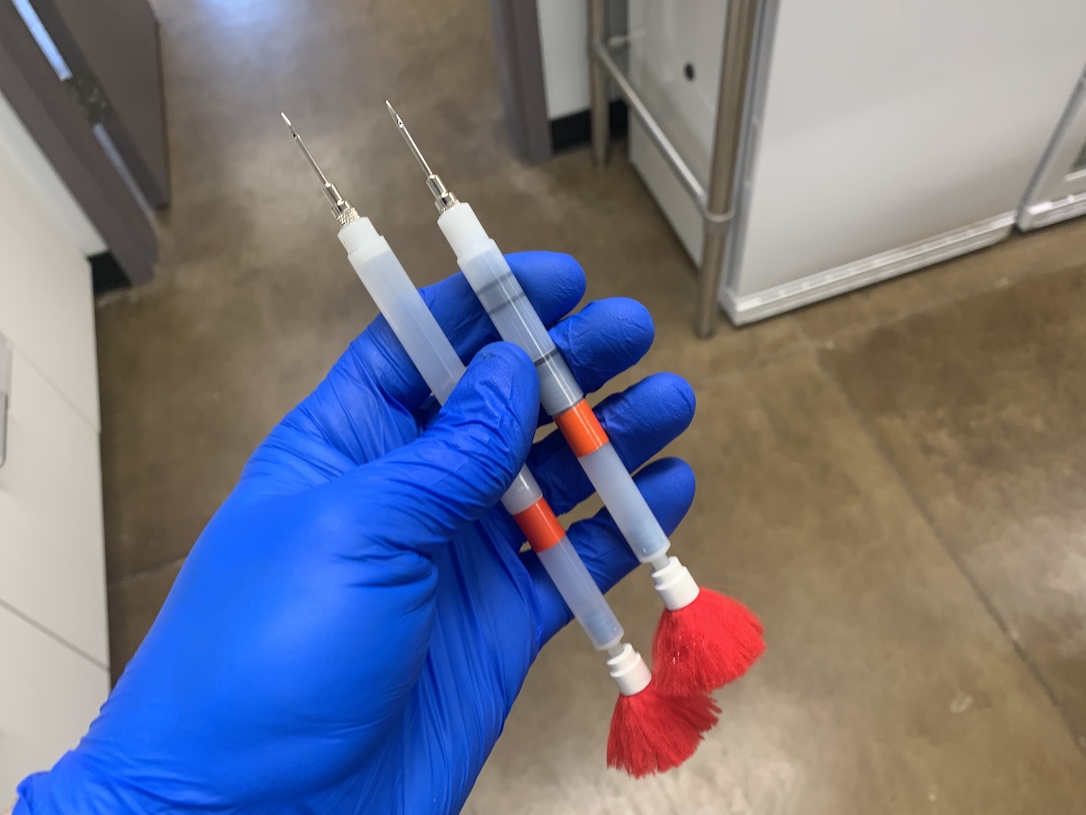

Dan Low, MD and Leah Bezzo, CRNA, both with Seattle Children’s Hospital, kept Willy safely under anesthesia. Tom Lendvay, MD, a urologist with Seattle Children’s, performed the initial evaluation with ultrasound assistance from Korey Krause, RDMS.

Willy also had a full cardiac workup, including chest radiographs and an echocardiogram by Marneye Driesen, RDCS, since some forms of heart disease can cause fluid to begin backing up in cavities such as the scrotum.

While he was under, Willy was also given a complete abdominal ultrasound.

Echocardiograms require a more powerful ultrasound machine than the one we own, so we are very grateful to the Woodland Park Zoo for once again allowing us the use of their machine. The machine was delivered to the sanctuary by Barbra Brush, LVT, who also participated throughout the procedure, including giving William a thorough dental cleaning.

The results of the echo and samples from his scrotum will have to be sent off for analysis but based on what we’ve seen, Dr. Erin has reason to believe that Willy B will benefit from some cardiac medication, just like his buddy Cy and like good ol’ Burrito across the way.

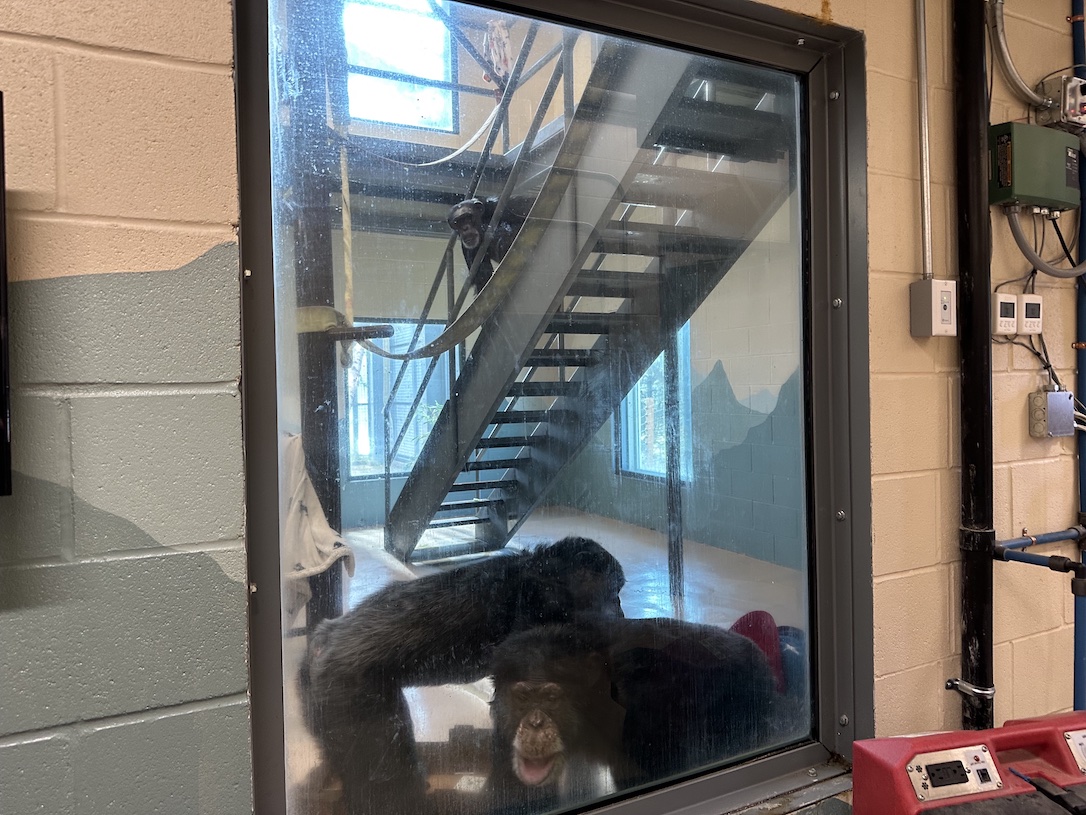

Willy did great throughout the procedure and is recovering quickly – due in part to the fact the we have kept his feet nice and warm and fashionable. We think it’s also due to the fact that he has a standing 2:30pm appointment to display and cause chaos in his group, to which he has never once been late.

Thankfully, he also seems to understanding the importance of getting rest after a clinic visit, so we’re hoping that he’ll take an afternoon off just this once.

Many, many thanks to this amazing team of medical professionals who traveled great distances to join us this morning and of course to our own Dr. Erin and Grace! We will continue to seek the donation of a portable cardiac ultrasound machine but if that is not in the cards, be on the lookout for a fundraiser sometime next year 🙂

We’ll share updates about Willy B when we know more.