Primum non nocere.

It’s perhaps the best-known axiom of the Hippocratic Oath, which in various forms has served as an ethical guidepost for physicians since the 5th century BCE. Though the exact phrase appears nowhere in the oath itself, and would not appear until over two thousand years later in an obscure English medical text, the principle has been at the core of western medical ethics from its inception. It’s often explained as follows: “Given an existing problem, it may be better not to do something, or even to do nothing, than to risk causing more harm than good.” While Hippocrates almost certainly did not intend for his oath to be applied to nonhuman animals, I believe his admonition is equally relevant to the medical care of captive chimpanzees.

When I teach about animal welfare, I often draw on the work of David Fraser. In a paper entitled Assessing Animal Welfare: Different Philosophies, Different Scientific Approaches, Fraser reviews the ways in which people concerned with animals have traditionally attempted to promote welfare and summarizes their work into three main objectives: (1) To ensure good physical health, (2) To minimize negative affective states (e.g., pain, distress, fear) and to allow for normal pleasures, and (3) To allow animals to live in ways that are natural for their species. As he explains, the different levels of emphasis we each place on these objectives do not necessarily arise from different sets of facts but rather from applying different sets of values. In the sanctuary world, we often find that people involved in the care of chimpanzees share the same good intentions but weight each criterion differently according to their own unique roles and perspectives. For example, a veterinarian or vet tech may be apt to focus more on the prevention of illness and disease, a caregiver may be more attuned to the emotional state of the animals they care for, and a member of the public may desire to see animals living as close to their wild state as possible above all else.

The challenge we face in attempting to reconcile these different values is that our efforts to promote welfare as judged by one criterion do not always improve welfare as judged by the others. In fact, a single-minded focus on any single objective can lead, somewhat counterintuitively, to reduced states of welfare overall. A classic example of this concerns food. If you want to make a chimpanzee happy, give them something to eat – they will grunt, squeak, and scream with delight. But focusing on this strategy alone and without reasonable limits will eventually lead to poor health in the form of diabetes, heart disease, or other potentially preventable ailments. The same is true for strategies involving natural living. If we choose to deny shelter from inclement weather to the animals in our care just because their wild counterparts don’t enjoy the same advantage, we contribute to avoidable suffering. These examples illustrate how genuine efforts to promote happiness or natural behavior without adequate concern for the other objectives can have the counterproductive effect of decreasing welfare. The same can be true, I would argue, for our attempts to promote physical health through frequent routine exams under anesthesia.

Sometimes I daydream about a world in which we can take the chimps by the hand and walk them into a clinic for a routine physical – just roll out some of that paper on the exam table, plop them down on their butts, and give them a thorough evaluation. If we don’t find anything wrong, we can give them a lollipop and send them on their way back to the sanctuary.

The reality of providing medical care to chimpanzees is, of course, very different. I should state at the outset that much can and should be done cooperatively through positive reinforcement training (PRT). We can treat wounds, take temperatures, collect urine for analysis – even obtain some x-rays – all while the chimpanzees are awake and safely situated on the other side of a barrier. Some captive chimpanzees are even trained to allow blood draws and cardiac ultrasounds through the mesh. But most have not been trained to such an extent, either due to their personal histories or the finite resources of the institutions in which they live. And there are some procedures that cannot be done properly through the mesh regardless of training. Sure, you can try to palpate an awake chimpanzee’s abdomen but you might not get your arm back.

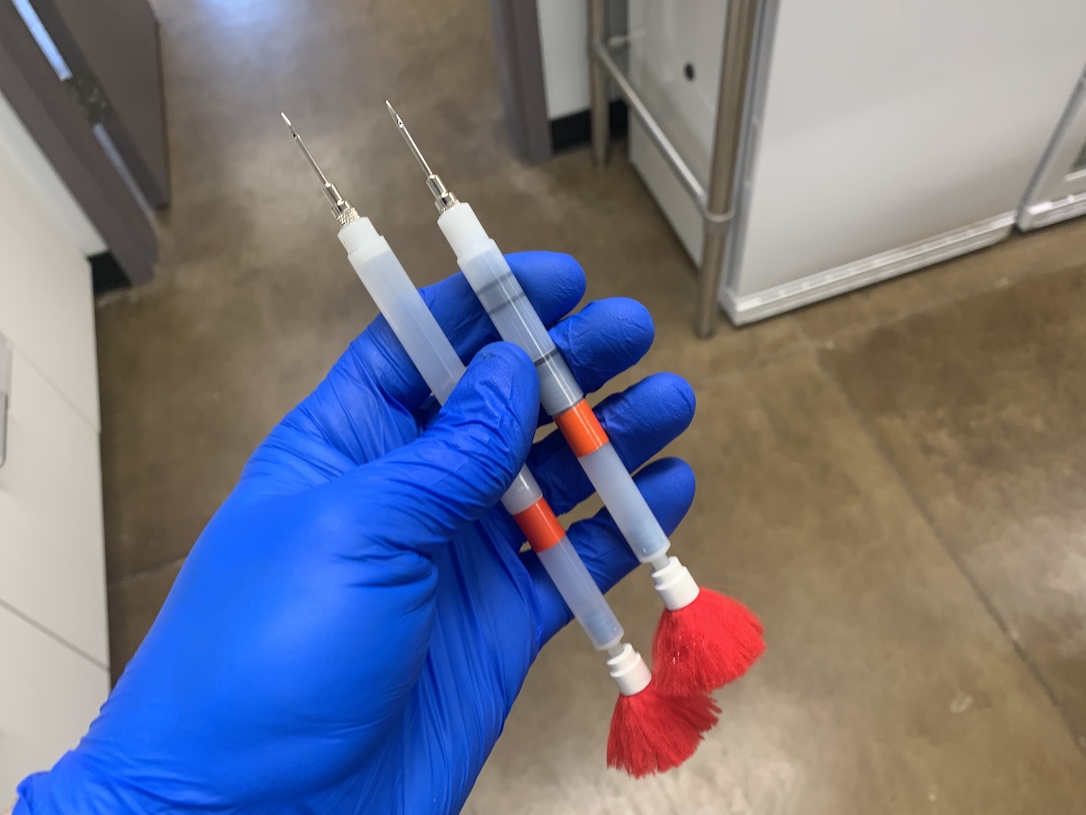

In order to conduct a thorough physical examination, a chimpanzee must be anesthetized. If the thought of anesthesia has you imagining yourself laying in a hospital bed with a mask over your face, attempting to count backwards from one hundred as you peacefully fade from consciousness, you are definitely not a chimpanzee, because chimpanzees have to be anesthetized before they even make it to the hospital. We accomplish this by way of intramuscular injection, which can be administered in a number of ways. Ideally, we use PRT to desensitize them to the stick of the needle and the sting of the injection. They will then learn to present a shoulder or thigh to the mesh and hold still until the injection is fully administered. Jamie and Honey B are among our resident pros at this. When chimps don’t willingly comply but don’t run away either, we can sneak an injection by hand when they aren’t paying attention. Jody can’t bear the thought of watching us inject her but she remains curiously close to the mesh as though she knows what has to happen. Still, her scream betrays her true feelings on the matter. Then there are the chimps that won’t go down without a fight – otherwise known as Burrito. When a chimpanzee must be anesthetized but won’t cooperate, we are forced to use the dart gun.

Hollywood has done a terrible job at depicting remote anesthesia. Many people think of darts as nothing more than sewing needles with red tufts on the end, but anesthetics aren’t effective in such small volumes. We pay good money to have some of our anesthetic drugs compounded at specialized pharmacies so that they are higher in concentration, and thus effective in smaller doses, but the smallest dart we can get away with is still 1cc. And some situations may still call for a 3cc dart. The needles on these darts are gauged to allow the drug to be ejected in just a fraction of a second, lest the dart bounce or be pulled out before the drug is fully delivered, which means that they are large and cause significant pain. I’m sure you know from your own visits to the doctor that injections are typically given in well-muscled parts of the body. This is partly due to the biology of drug absorption but it’s also for your safety. You definitely don’t want to get poked in a bone or major nerve. I once gave myself a needle stick injury with a clean needle in my fingertip (while demonstrating pole syringe safety…ha!) and years later I still have numbness in that finger. Safely darting a chimpanzee requires us to hit a target measured in square inches from a distance of several feet or more – all while the target moves quickly and unpredictably. You can never truly appreciate just how puny Burrito’s little butt is until you’re trying to land a dart in it. Fortunately, the majority of my darts have been on target and all appear to have caused little to no injury, though if they were to cause an injury like the one I gave myself, how would anyone know?

We employ a number of strategies to help take the edge of the process. A sip of Valium-spiked juice an hour or so before induction can ease their anxiety, and ketamine lozenges or medetomidine-laced peanut butter can even initiate the induction process prior to injection. But eventually they have to go down, and that process is itself often traumatic. We try to conduct all of our “knock downs”, as they are referred to in lab parlance, in a small room with no furniture so that they’re less likely fall and hurt themselves. But they still do on occasion. Waking up is no walk in the park, either. Some chimps experience what’s known as a “stormy recovery”, which can involve anxiety and hallucinations. These effects can usually be mitigated with the use of additional drugs, but a few chimps seem prone to them regardless. And many of the drugs in our toolkit are contraindicated based on a chimp’s age, weight, or clinical history, leaving us with fewer options.

Anesthesia has become relatively safe in human medicine, but it is rarely done without good cause and it is still dangerous enough to require a specialist. While we lack good data for other great apes, the rate of complications would appear to be far higher than in humans. I keep a document on my computer in which I note instances in the public record of great apes dying during routine examinations. Currently, the total stands at 24 great apes since 2003. I would guess the actual number is several times higher, since it’s not exactly the kind of thing you run out and advertise if you don’t have to. Of course, we must ask: out of how many in total? It’s hard to say, but there simply aren’t that many great apes in zoos and sanctuaries. In each unfortunate case, it’s noted that the ape went in for a routine physical and never woke up. Underlying heart disease is often blamed, which is probably accurate in most cases. It may be a relatively small risk overall, but it is one with a severe and irreversible consequence.

Is it all worth it? That is, in the absence of a clinical concern, is it right to subject the chimpanzees in our care to the risks and trauma of anesthesia – and in some cases, to abuse their trust and further deny their autonomy? Are we justified in subjecting former lab chimps like Jody to more knock downs when they had already suffered through dozens, even hundreds, before ever making it to sanctuary? Would we do the same if they were not chimpanzees but instead members of our own species? According to Fraser’s framework, it would be equally misguided to forego routine examination under anesthesia solely on the basis that it causes fear and pain. It’s our responsibility as caregivers to find a point of balance. Doing good sometimes requires doing harm, as we all know. But making that calculation requires us to wrestle with the risks and benefits of all possible actions, as well as inaction.

What do we hope to achieve through routine physicals? We can gather a significant amount of information about a chimpanzee’s health through daily observation. Are they eating less? Losing weight? Chewing on only one side of their mouth? Sleeping more? Are their gums bright and pink or pale and gray? Has their respiratory rate changed? Positive reinforcement training for cooperative medical procedures further expands the amount of information we can obtain. What should concern us, then, are those things that remain outside of our ability to diagnose through cooperative means and do not yet present any clinical signs. I’ve spoken to many colleagues and asked what they’ve discovered during routine exams that was both surprising to them and, importantly, led to treatment that reduced suffering and/or prolonged life. And to be sure, there are examples – preclinical heart, kidney, and dental disease most prominent among them. It probably goes without saying that chimpanzees are less able than most humans to share what they are feeling internally when clinical signs are absent.

Let’s stipulate for a moment, then, that routine exams are a net benefit. How often should they be performed? Many Americans are accustomed to the idea of annual physicals, but the practice was largely a product of the medical insurance industry in the 1940s and by the ‘80s most medical professional groups were advocating for a less rigid and more tailored approach. After all, the earth’s orbit around the sun has little direct association with the development of disease. Clearly, other factors like age, sex, clinical history, and the rate of progression and window of opportunity for treatment for diseases of concern would be better guides. And remember, our framework for promoting welfare should caution us from thinking that if some is good, then more is necessarily better. I was once alerted to an online discussion in which someone stated proudly that their institution conducted physicals on their prosimians every three months. It’s possible given their size that the exams were not all conducted under anesthesia, but is that really beneficial under any circumstances?

What, then, is the correct interval? Two years? Five years? Or only as needed? I must acknowledge that my views are at least in part the product of my early influences. The institutions that I worked at prior to CSNW did not conduct routine exams. And one of the Cle Elum Seven’s original veterinarians, Mel Richardson, did not advocate for them either. Dr. Mel was an animal’s friend through and through. He began as a zookeeper and later became a veterinarian for several AZA-accredited zoos, including Zoo Atlanta and nearby Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle. He served as a veterinarian for wild gorillas in Uganda and directed an orphanage for rescued gorillas and bonobos in the DRC. He went on to serve as an expert and consultant in some of the most high-profile animal rescues and animal rights court cases in North and South America. Before CSNW had taken in a single chimp, I asked him, “Do you think we should conduct routine exams?” His answer? “I have never found them to be worthwhile.”

I also can’t rule out that my own personal discomfort with the process affects my views. It can often be unpleasant to inject or dart a chimp, and there’s nothing fun about listening to the various chimes and alarms of the anesthesia machine during an exam or watching them struggle to make sense of where they are and what happened to them during recovery. Of course, my own discomfort should not be relevant – we all have to do things we don’t enjoy. But if it makes me uncomfortable, I can only imagine how the chimps feel.

Today, CSNW relies on a team of veterinary professionals, led by the incomparable Dr. Erin, that includes veterinarians, vet techs, physicians, and nurses, all with impeccable credentials and unwavering dedication to the chimpanzees. And yet we continue to debate, in good faith, the value of exams in the absence of clinical concerns. Some believe, as Dr. Mel did, that we should only intervene when we have a clear reason to do so. Others feel that the risks of inaction, at least in some cases and at some intervals, outweigh the risks of complications and trauma of anesthesia, and I trust them every bit as much as I trusted Mel. Each of them is right to believe as they do. Same facts, different values. No easy answer.

The system that we settled on to help us navigate this dilemma is to conduct Annual Health and Behavior Evaluations. Anthony, CSNW’s Health and Behavior Coordinator, compiles a summary of relevant information from our medical database for each chimpanzee – age, sex, the date of their last exam, ongoing health issues or concerns, the status of their cooperative medical behavior training, health data such as weight measurements, radiographs, heart rates from PRT sessions, etc. – and sends it for review along with a survey to the staff. Survey questions are designed to solicit feedback on medical and behavioral concerns from those who know the chimpanzees best, from their relationships with other chimpanzees in their group to the presence or absence of stress-related behavior. Results are then reviewed by a medical and behavioral committee along with the chimp’s file and a health plan is formulated for the upcoming period. These plans could include changes in diet if a chimpanzee has gained too much weight, training for specific behaviors if more health data is needed, such as urine collection from an aging female chimpanzee to help monitor kidney function, or increased enrichment for a chimpanzee that exhibits boredom or inactivity. The plan may also include scheduling a physical exam if one is deemed worthwhile based on the individual’s history and clinical status. But there is no requirement for one, and no fixed timeline. We are still left to rely on judgment and consensus, albeit through a formalized process tailored to each individual.

Do you ever have a strong opinion about other people’s opinions without having a strong opinion of your own? When I hear people say that chimpanzees should be given frequent exams under anesthesia, I am convinced they are wrong. I am far more sympathetic to the idea that routine physicals without clinical concerns are never warranted, though I am plagued by doubts – what if we miss something that could have been treated? I can play devil’s advocate all day long for any argument on the subject but I can’t tell you exactly what I believe.

I want to make clear that we never hesitate to intervene when a chimpanzee is sick or injured, and any chimp that ends up in the clinic for a known illness or injury receives a detailed and thorough exam opportunistically. In the absence of clinical signs, however, we need to acknowledge the harm we cause and place it into a context that considers every aspect of a chimpanzee’s well-being – their physical health, their happiness, their sense of security, their trust, and their autonomy. We need to take stock of what we can learn through cooperative means and determine if what remains is worth the cost of anesthetic intervention. And we must somehow learn to balance the potential harms of not doing enough with the known harms of doing more than what is necessary, as Hippocrates so wisely advised. Whatever we decide, we will at times fail, because there is no perfect way to care for animals as powerful, strong-willed, intelligent, and independent as chimpanzees in captivity. Acknowledging that fact seems like a good place to start.

You all do such an amazing job. Bravo!

Thanks, JB. So Jo is recovering?

Hi Linda – These photos are from 2020 and are just examples to illustrate the story. I’ve updated the captions to make that clear.

Thanks, JB, sorry if I started something. I thought it might have been, because of the toe.

this is an absolutely wonderful blog post. I doubt very many people realize what’s involved with treating these guys and keeping their health up to par. thank you for the work you do and thank you for publishing this. I’m going to be posting this on Facebook so everyone can read!

J.D.,

I always appreciate your blog postings elucidating, both in how they convey scientific information as well as how you articulate ethical concerns. Regarding the photographs and text, I must ask: Did Jody undergo a medical procedure today (1.21) or recently? If so, are you at liberty to divulge the health concern? I know that a few years back that an examination was conducted regarding a growth on her foot.

Hi Tobin – I’ve edited the captions to hopefully make it clear that the photos are old and are only included to provide illustration to the article. Jody is doing great!

I am much relieved to read that, J.B. My gratitude to you and to all of the staff for taking such thoughtful and compassionate care of my dear Jody and all of her friends and neighbors who live at the CSNW

I love this blog. Very informative and lot of food for thought. I know how badly I feel when I have to ambush one of my cats to get him or her in the carrier to go see the vet. I can just imagine how it might feel to have to dart a chimp. Thank you all for taking such wonderful care of these beautiful creatures.

That was a great article and what a lot to think about.

I think anyone who has a pet goes through some of these same issues. I’m not including chimps in the pet category! My last guinea pig’s health was never up to par because of overbreeding. For some of her tests I had to make decisions about anesthesia. It is a very risky thing with them also and they don’t always pull through. Than there were blood tests and an ultrasound. There was only so far I was willing to go before I had to just accept the inevitable and give her the best of the time she had left. It was hard because I wanted to keep going but that would just have been selfish on my part. Loving animals is a tough road sometimes and we are the ones who have to make some difficult decisions along the way.

On a lighter note I can only imagine plopping Jamie’s butt on an exam table and giving her a lollipop!

Thank you, J.B., for a great post! i always learn something from you. The time and effort you put into today’s post is well noted and much sppreciated.

i loved reading this. The decisions you make are so weighted and important. The back and forth in this post reminds me of parenting and how we differentiate decisions based on the needs of the specific child. My average sons get different medical care than my daughter with medical PTSD. It stops being a matter of routine and becomes founded in observation and necessity. Thank you for letting us wander through your thoughts and prioritizations. You are doing a beautiful thing at CSNW.

Given all the thought and care that you have laid out here, I can honestly say that I have complete and total trust in your judgment.

I Totally Agree With That Statement!!

J.B. what an excellent presentation of the facts and dilemmas that are a routine part of what each human member of CSNW considers (to a greater or lesser degree) every day as you all go about your already intensively involved day/s. I have rescued pet critters of various types all my life. Usually I have a number of elder care situations going as many live out what time they have remaining here on earth with me as sole decision maker on this topic. While not comparable to chimpanzee care I fully understand . . and for what it’s worth my 63 years perspective is 100% in line with yours. You all are amazing, what a blessing to have team input to your decisions. Thanks to all of you.

What an articulate, well thought out and interesting article. As you have been influenced by Dr. Mel, so have I been influenced by you. It is apparent that your critical thinking skills have been well employed. Thanks, J.B., for taking the time to share with us.

Thank you so much for this thoughtful and educational post. The CSNW chimps are lucky to have ended up in your care.

When I consider what the lab veterans went through being darted, daily, screaming in fear, it would break my heart to have no other choice. I’d like, wishfully I suppose, to think that those nightmares have faded some over the years, but when humans experience a tragic childhood, or a woman an assault, the effects can last a lifetime. We have no.waynof knowing. It is certainly a fraught dilemma. What I am sure of, however, personally, is that if the stats show one captive gorilla dying every year during a knockdown, there is something very wrong happening.

i should qualify. my concern about the gorilla knockdowns is that they were routine exams. One has to ask if they were necessary. 🙁

As the others have, I agree with congratulating you on the value of the blog. So hard to make medical decisions for another. The sheer volume of work you have to do for each chimp, multiplied by 16 or 20, to include the cattle, is incredible. So glad the chimps don’t seem to have affected them now.

great blog, JB. some of these decisions are so hard to make. i tend to agree wtpith Dr. Mel. I remember that guy with so much admiration and respect. again, thanks to you & Diana for all your hard work.

I can read your struggle to know if you make the right desicion every time J.B.

And from one human to the other I say to you: Yes You Do! because it is so well thought through, looked at from every angle and taken from the heart. You are a good person and you are (ALL of you) doing such a tremendous job looking after the residents of this wonderful sanctuary.

I was pleasantly surprized to see good old Jody sitting still with her foot in the box while you and Diana take a X-ray… well done!!

Thanks for such a thoughtful commentary, which lays out many of the nuances when it comes to medical decision making for animals in one’s care. I have always admired the personal attention CSNW is able to give each chimpanzee. Your commitment to positive reinforcement training means that chimpanzees are empowered to participate voluntarily in much of their medical care, preserving their autonomy.

I think one of the strongest arguments for routine anesthetized exams is that they provide the opportunity to provide dental care to curtail periodontal disease, which can cause of both pain and harmful effects on other organs in the body. Working as a veterinarian at other sanctuaries, I frequently saw chimpanzees with cavities and tooth infections. Low sugar diet and routine dental hygiene (e.g., teaching chimps to brush) can definitely extend the intervals between anesthetized dental exams and cleanings, but not eliminate the need for them.

At a sanctuary in Cameroon, I learned a very gentle anesthesia technique for chimpanzees. It involved administering dexmedetomidine, mixed with a little bit of juice powder, transmucousally over 10 mintues. The chimp would fall asleep and then could be hand- or pole-injected with ketamine or another anesthetic. It requires some preparatory training to accept juice one drop at a time via syringe, and obviously would be a bad choice for a chimp with heart disease, but for healthy youngsters or young adults, it was wonderful – as close to zero stress as you could get.

I think larger sanctuaries, especially those that accept new primates periodically or that don’t have a strict health program for human caregivers or visitors, also need to consider more frequent anesthesia for infectious disease testing, like tuberculosis. Some primate sanctuaries in Africa have been forced to virtually depopulate due to TB spreading through their groups. This is less of a concern in the US, but other diseases may be a concern depending on where the chimpanzee originated and whom he or she lives with.

Finally, I think we do well by chimpanzees when we make any anesthesia we choose to undertake really “count” — providing dental care, efficiently completing a battery of diagnostics tests perhaps beyond the issue that is the main focus– to avoid having to anesthetize again in the near future.

Chimpanzee sanctuaries, and their delivery of medical care, are importantly different from the lab and zoo settings where many opinions on anesthetized exams have orginated. I think it is great that the sanctuary community is continually reflecting on issues like these and striving to provide optimal welfare, holistically conceived, and support the autonomy of their chimpanzee residents.

It’s great to hear your feedback, Gwendy. Yes, we’ve spoken with Sheri about that technique and have experimented with it but given the average age of our population it’s not something that we’ve felt comfortable adopting across the board. Another vet that we consult with often uses the same approach but administers the dex IM. Because the volume is so small, and dex doesn’t sting like ketamine, that part of the cocktail can be injected almost anywhere on the body with a tiny needle, to be followed buy ketamine later. It’s great that people are finding ways to take some of the pain and stress out of the process.

I would love for the sanctuary community to discuss in more detail the types of findings you are describing. What is the average timeline for the development of periodontal disease? How long does it typically take undetected and untreated periodontal disease to cause pain and discomfort and lead to sequelae? How does it vary by age? Etc, etc. These things should inform decisions about intervals between exams. If Foxie got a dental exam and cleaning while under anesthesia for an unrelated illness, should we expect things to change significantly in 12 months? 24 months? It’s certainly possible that these conversations are happening and we’re just not part of them, but if they are we should elevate them so that more institutions can take part. Perhaps it’s something that NAPSA could lead. Which means I shouldn’t compain and should just do something about it besides writing a blog post 🙂 Maybe you should expect a call before our next NAPSA workshop…

That kind of research sounds like a great idea! I’ve seen a few studies on primate/chimpanzee dental disease, but not many. Few sanctuaries have dental X-ray capacity, so it’s possible some painful lesions are being missed as well. I bet you could find a vet doing a dental residency to take something like this on as a project. Or maybe someone through the Peter Emily International Veterinary Dental Foundation?

The topic of decreasing stress associated with inducing anesthesia is fascinating as well. I’ve been following the increasing use of gabapentin as an anxiety-reducing drug to facilitate medical exams and anesthesia procedures in a range of species, including pediatric human patients.

As far as I can tell, gabapentin has been used in chimps mostly for neuropathic pain. But, based on how helpful it is in other species, it seems promising as a safe, cheap, easy-to-administer medication that could help make sedation much less stressful for chimps, and maybe even decrease the drug doses needed to induce anesthesia. The less we need to rely on darting, the better!

Sanctuaries have really been pioneers in decreasing the stress and unpleasantness of sedation for chimpanzees, and I hope to see this trend continue! Don’t hesitate to reach out if there’s anything I can do to help 🙂

JB, I concur w/ others’ responses about your wonderful, educational posting. I much appreciate the time and effort it took to provide us with this information, including your depth of perspective and years of training. I’m so grateful for the thoughtfulness and expertise that you and the entire staff bring to your work. It’s also good for me to have the important reminder that it’s not all blankets, boxes, toys and food puzzles. What we mostly get to see and experience are the day-to-day lives of the chimps’ various goings-on. It’s wonderful and often the highlight of my day. The behind-the-scenes efforts of what it takes to keep all that going, address the all-important health/medical concerns & needs that you talk about, prep food, pay the bills, address the cleaning complexities of their spaces, etc. remains mostly out of our daily awareness. Bottom line: Thank you to the whole staff for your commitment, training and expertise that enable these chimps to live the best lives they’re able. I’m so grateful for this entire community, including donors, people who respond on this blog and the board who exist “off stage” but provide a strong foundation for the sanctuary’s solid present and future, including having hired you and Diana!!

What an extraordinary post J.B.! I had to save it to read when I could sit quietly to fully absorb and appreciate it. It sparks a desire in me to attend classes taught by you. Oh to partake in your teachings via my computer on zoom or something similar — a fly on the wall so to speak! Where can I sign up and what’s the tuition?! 🙂

This post should be published for everyone in animal welfare/wellcare to read. Even if an animal is not “as powerful, strong-willed, intelligent, and independent as chimpanzees in captivity” (as you stated), all of your concerns are very valid and we should stop and reflect on the matter. Many of your concerns apply to our companion animals as well.

Because chimpanzees have been knocked out so many times during their unfortunate time spent forced to exist in biomedical laboratories, I can’t help but wonder at what point do you or could you reach “one too many”? We can’t know because every individual would have a different level of tolerance and even that could change with age and other factors. There is risk in anesthetizing any living individual, especially those who have knocked out hundreds of times. A frightening reality.

I often choose to sit with shelter dogs who, after their various surgical procedures, return back to the shelter. These dogs are still knocked out or super drowsy upon return. Some bounce back quickly while others appear to be suffering as they come out of their drug haze. For some, it takes a very long time. It is painful for me to witness because they yelp, shiver and shake, moan and cry, toss and turn, all of this turmoil taking place with me squished into their blanketed bedbox, sitting with their head on my lap while I stroke their soft heads and whisper in their ears hoping they can feel and hear me and find some comfort from my presence. I can tell you this much with certainty, those dogs remember me from that point on. But you can’t do this with a chimpanzee.

There is no soft, comforting approach to darting. Even when if that dart comes from a person you trust and love. With no comfort to offer a strong wild-captive-animal, like the hands on reassurance we can offer our companion animals, how can you help your chimpanzee friends cope with their fears and anxieties and understanding that is for “their good”? Sigh. You must feel a little helpless, or should say I would feel helpless in this situation. It must be very stressful on everyone involved. And I’m assuming the chimpanzees, much like dogs, feel the humans stress. All the more reason to proceed as you do and save extreme measures for the more extreme circumstances.

I support your sanctuary because I know you never do anything lightly. You bring your head and heart to the table every time. You go above and beyond. I believe those in your care understand this at some level too.

We used to play a game at the shelter where we would ask each other “If you had one thing you could tell/teach a shelter dog, what would it be?” My answer was the same for my favorite shelter dogs as it was for my adopted dogs. I would want them to know that they are safe and loved in my care. Always. No matter what. And that I may not always “get it right” but I will always give them my very, very best. I so want them to understand this. If only it were that simple……

What initially drew me to CSNW was the smaller number of chimpanzees relative to other sanctuaries, as I felt the chimpanzees received more personal attention, be it with play, enrichment or healthcare. Also, I can “know” your chimps. (my chimps;) ) That’s very difficult to do with the large sanctuaries.

Marya, me too! re this community.

Kathleen, it’s wonderful that you sit with animals coming out of surgery. A couple of years ago I went around to three animal hospitals nearby to volunteer to do just as you described. unfortunately none of them would allow it, for liability reasons. I was very disappointed and actually confused because I thought those places needed volunteers to do just that. But… Sigh

Paulette, that’s exactly why I follow this place so closely, too!

:thumbsup::slight_smile:

I appreciate all the detail and tech info here. It’s always fun to hear about what the Chimps have been up to each day, and it is also valuable to hear these other angles about their care. I didn’t know Dr Mel’s background! Also, the mentions of him reminded me of the Gala when the video of first moments on the Hill was shown, and Dr Mel “doing the Burrito” dance at the podium. xo

Thank you for being forthright and honest about the complexities involved in decision-making at the sanctuary. Refreshing to read about an organization’s story that is not condensed into a binary sound bite. i appreciate the context, history, and bias that you acknowledge. Well written and thought-provoking.

You have a really good team. I know you are taking the best care of these chimpanzees that is possible and I know you care greatly. I know because I see how happy and responsive they are in spite of what they have been through. I also feel that there are not many other options. Unfortunately we are all dealing with the results of careless exploitation in the past (actually ongoing to be accurate}. We can’t make it right but we can make intelligent choices as we carry on. Thank you all very much.