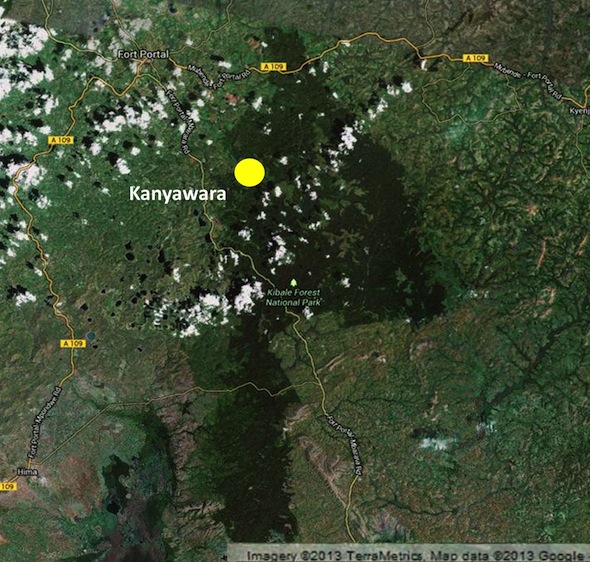

Dr. Zarin Machanda is one of our guest bloggers who is doing a series on the chimpanzees of Kanyawara in the Kibale National Park. Read her introduction post here, to use as a little background for this post about the research they do in the wild. The Kibale chimpanzees were also mentioned in our latest guest blogger post from Maureen McCarthy, a heartbreaking story about a chimpanzee caught in a snare trap. In Kibale, they have snare removal projects and work to help save chimpanzees. Find out more about them here.

—

And now, for the second installment of Zarin’s series:

Hi everyone – I’m back to tell you a little bit more about the chimpanzees of Kanyawara. Today, I thought I would write about some of the different research projects that we have going on. But first, a quick update from the field – it seems that Eslom is prevailing against Lanjo in the quest for alpha male status. I know I shouldn’t be disappointed because alpha male transitions are rare (this will be the 4th in 26 years of observation at Kanyawara), so any new observations are bound to be interesting. But why did it have to be Eslom?! I mean, he’s scared of having his picture taken!

The only photo I have ever managed to take of Eslom. As soon as I pulled out my camera, he went and hid behind a tree. I managed to get one shot of him peeking out before he got spooked. Alpha male material? I’ll let you decide.

I still have faith that Lanjo is just biding his time and waiting for Eslom to get tired of running around causing havoc. And who knows – there could always be a surprise candidate waiting in the wings: Big Brown, a former alpha wanting to relive his glory days or maybe even dark horse, Makoku. Don’t let that floppy lip fool you, this 30-year old was high-ranking before Kakama died.

Two more potential, although unlikely, candidates for alpha male. Big brown (left) was alpha in the mid-1990s but since he’s over 40, I’m not sure he has the fight left in him. Makoku (right) has an older brother Johnny in the community who might prove to be an ally if he decides to go for alpha status – but so far, he doesn’t seem that interested. Photo courtesy of Ronan Donavan.

As a research group, we are particularly interested in male dominance and male relationships, so this change in the hierarchy will yield incredibly valuable data for us. Among chimpanzees in the wild, adult males are socially dominant to all the other individuals and they are also much more gregarious – adult males like to be in parties together whereas adult females tend to spend more time alone with just their dependent offspring. Adult males also exhibit more cooperative behaviors like boundary patrols and hunting and we think that tend to have strong relationships with one another to facilitate this cooperation. One of my research interests revolves around understanding how and why individuals form strong long-term social relationships with one another. But to do that, we have to figure out how to identify relationships. Of course, it would be easy to just go with a gut feeling – sometimes you just have a sense watching individuals that they are great friends or that they don’t like each other. But as scientists, we need an objective measure that others can replicate. So how do we measure friendship?

A pile of male chimpanzees grooming each other. Adult males form very strong bonds with one another and we often use grooming behavior as an indicator of a bond. The chimpanzees at Kanyawara also engage in a behavior called hand-clasp grooming where they raise their hands and clasp them above their heads while grooming each other. Not every chimpanzee community exhibits this kind of behavior and we think that this might be a cultural variant of grooming. Photo courtesy of Ronan Donavan.

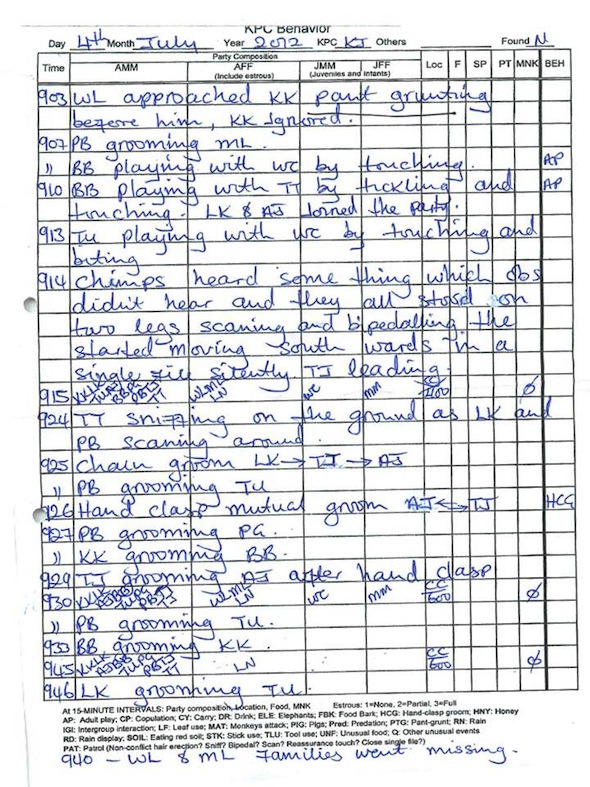

Well first, we have to collect systematic data on the behaviors and activities of the chimpanzees. At Kanyawara, we employ 6 full-time Ugandan field assistants who enter the forest almost every day to collect our long-term field data. We still prefer the old-fashioned method of pen and paper data collection – just like Darwin used to do! One type of data involves identifying all the individuals present in a party every 15 minutes and then writing down the time and description of any interesting behaviors (e.g. grooming, copulations, etc.) that occur. At the same time, another field assistant collects data on one specific individual in the party and records their activity every minute, and who they are sitting near every 15 minutes. From this data, we can figure out which individuals spend time with each other in parties, sit next to each other and groom each other most often. Combining these measures, we can identify individuals with strong bonds. I like to think of it this way – you wouldn’t spend a lot of time with someone you don’t like (let alone let them groom your private parts) and we don’t think that chimps do either.

An example of some of the data that we collect. Our field assistant, James, was following a large group of chimps that morning. Around 9:00am there was a lot of social activity including some adult males like Big Brown (BB) and Tofu (TU) playing with some young individuals. Then at 9:14am, the chimps heard something and appeared to be cautious but interested. As they moved south towards the sound – possibly the neighboring community of chimps – the males started grooming each other a lot while some of the females and their families left the party.

Dr. Richard Wrangham started our research site in 1987, so we have over 25 years of this kind of data which means that we can look at relationships over very long periods of time. Our research has shown that not only are males strongly bonded to one another, but almost every male has at least one really close associate – kind of like a BFF, except we call them PSPs (preferred social partners) and these relationships on average last for years. For example, we know that Makoku and his older brother Johnny are PSPs and they have been since at least 1995. As maternal brothers, they share a lot of genes in common and it makes sense that they have a strong bond because from an evolutionary point of view, you should support individuals who share your genes. If they succeed, it’s like a part of you has succeeded as well. By the way, Johnny and Makoku (as well as their mother Lope and sister Rosa) have floppy bottom lips, so there are definitely some shared genes there! It’s a little surprising to me that Makoku isn’t actively trying to be alpha male right now – not only was he the second highest ranking male before Kakama died, but he also has Johnny to get his back if anyone fights him. And Johnny is our biggest male chimpanzee, just the kind of wingman you’d want in a fight. Of course, Makoku could be trying to emulate his older brother’s style since Johnny never cared that much for being high ranking either. This seemed to work for Johnny – although the general pattern is for the alpha male (or at least high-ranking males) to sire the majority of babies in a community, mid-ranking Johnny is one of our most reproductively successful males and has fathered numerous offspring including Lanjo and Eslom. Does anyone else get the feeling that this is a little bit like watching a soap opera? The Days of our Lives: Kanyawara edition!

Johnny is Makoku’s older brother and has a floppy bottom lip just like the rest of the members of his family. Johnny has always been medium ranking, but surprisingly, he is also a real ladies man and has fathered a number of offspring. Photo courtesy of Ronan Donavan.

Besides studying long-term relationships, another area of research that Kanyawara has pioneered is the study of behavioral endocrinology. Basically, this involves trying to understand the interaction between the behaviors that we observe and the physiological processes happening inside the body that involve hormones. For example, one interesting question to examine right now is how testosterone levels of our adult males may be fluctuating given the instability in the dominance hierarchy. With all the aggression that Eslom is displaying, I bet his testosterone levels are through the roof!

As I mentioned in my previous post, we don’t physically interact with our chimpanzees unless their lives are in danger, so we can’t collect blood samples to measure their hormone levels. Instead, we rely on the urine and feces that they leave behind and it is remarkable how much you can tell about the inner workings of the body from a single urine sample. In our lab at the University of New Mexico, Martin Muller, Melissa Emery Thompson and their students use and develop techniques which can determine the levels of testosterone, estrogen, progesterone, cortisol (a measure of metabolic stress), and C-peptide (a measure of insulin). This means, of course, that we have to collect urine and fecal samples. This fun task most often falls on our field assistants, who have devised a very clever way to get the urine and not get too messy in the process. Basically, you have to find a long branch with a v-shaped end to it. Luckily, we work in a forest so these aren’t too hard to find. Then you take a clean plastic bag and tie it over the v-shaped end and voilà, you have made yourself a urine catcher! When a chimp is in a tree and starts peeing, you take your urine catcher and put the plastic bag end in the stream of urine. Once we have enough (only about 3ml), we can pipette the liquid off the plastic bag and into labeled tubes for storage.

A chimps-eye view of John, one of our field assistants, collecting urine using the handy plastic bag on a stick technique. The longer the stick, the less chance of getting splashed. Photo courtesy of Ronan Donavan.

Some of the hormone data that we have collected have changed the way that we think about the chimpanzees and their behavior. For example, the data from Kanyawara has shown that males who are higher ranking tend to have higher levels of testosterone. These guys are also generally more aggressive indicating that the testosterone may be mediating their aggressive behavior. These high ranking males also have higher levels of cortisol which means that they are experiencing increased metabolic costs – in other words, even though there is a benefit to being high ranking, there is also a significant energetic cost to it as well. This dataset has also given us a lot of information about females as well. Remember Outamba, the super mom chimp that I mentioned in my previous post? Well we know she is high ranking and we also have data to suggest that she, and the other high ranking females, have higher levels of estrogen and progesterone. This might be why she is able to have babies more frequently than the other females.

So that’s a little bit about some of the research we do on adult individuals. Next post I’ll tell you what it’s like to be a baby chimpanzee and some of the research that we do on our infants. Chimpanzees are so interesting and complex that I don’t think we’ll ever run out of research questions. Let’s just hope that we can also protect the chimps in the wild so that we can keep learning from these amazing individuals.