The chimpanzees’ world is full of color.

In the spring, the landscape blooms with eye-catching wildflowers and green foliage that seem to radiate color and warmth. Summers are characterized by deep turquoise skies. Crisp autumn days turn the surrounding meadows a shiny gold and decorate the surrounding forest with speckles of red, orange and yellow. Even now, in the deep winter, the muted skies and pale snow are overshadowed by the emerald tint of the numerous evergreen trees. Regardless of season, the busy Chimp House itself is always full of colorful blankets, enrichment, produce, tools, and even some sensible wall decor.

Despite all this light flowing around us, capturing compelling portraits of the chimps is usually difficult. For one thing, the chimps and humans are always separated by steel caging, a chimp-proof window or an electrified barrier. These structures wreak havoc on camera lenses and need to be focused out. Even when the chimpanzees are foraging or patrolling outdoors, they are often hundreds of feet away, obscured by dense foliage, or sprinting around the habitat (see: Missy). Sometimes, the bright sunlight creates harsh shadows that yield miserable photographs. Indoor lighting is also a challenge, to put it lightly, and using flash on an alert chimpanzee would be a horrible idea.

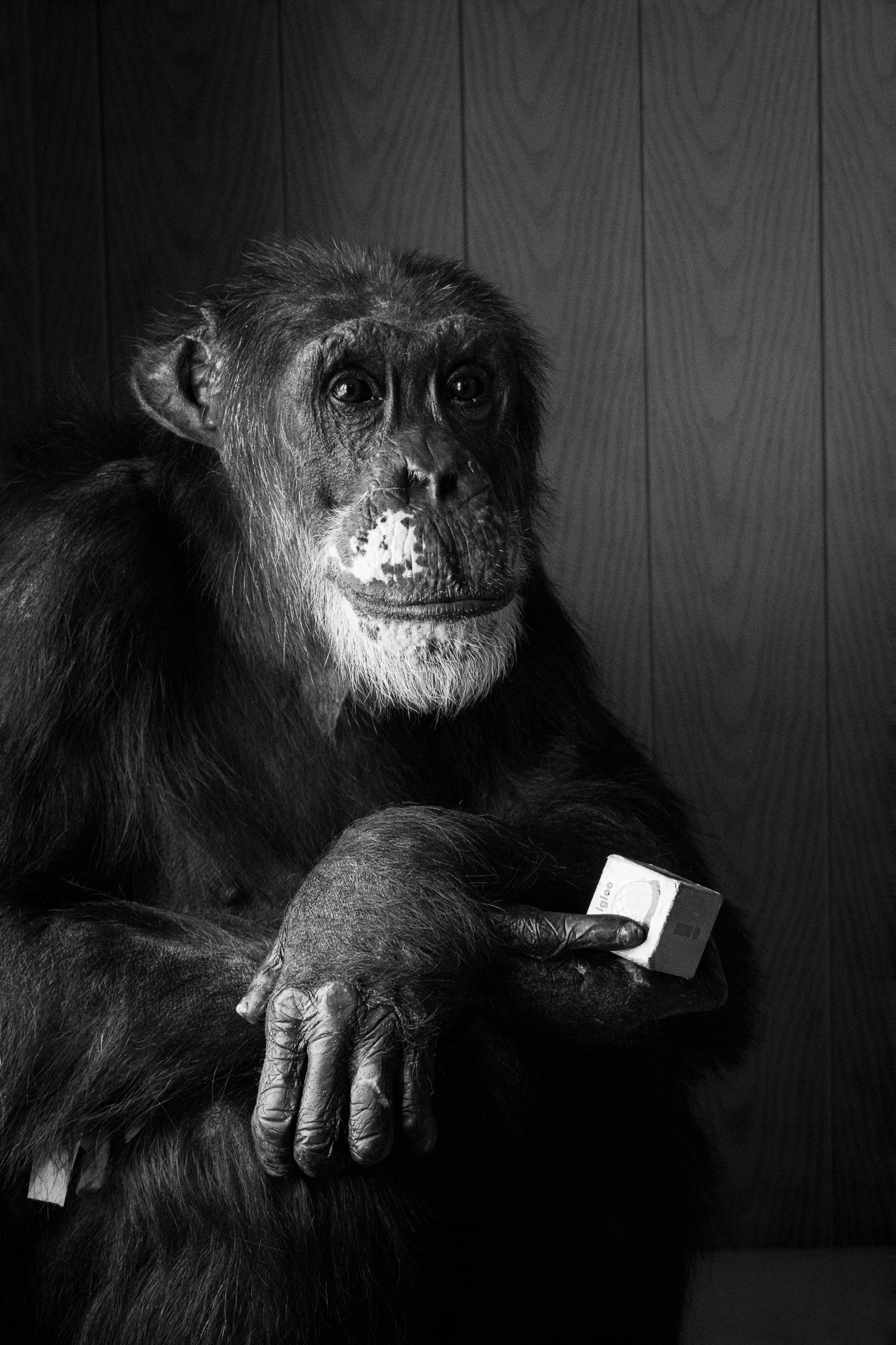

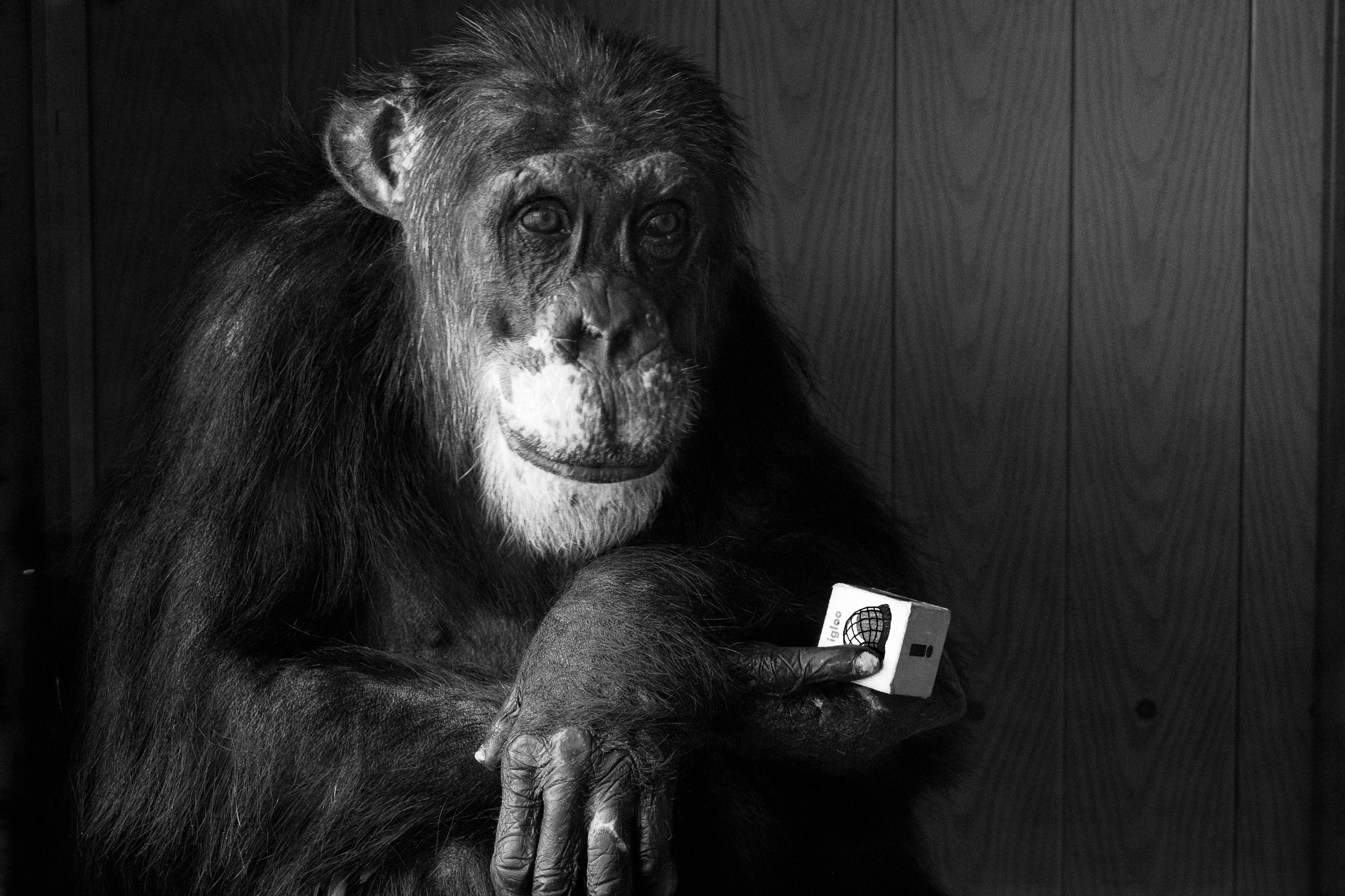

However, there is one place in the whole sanctuary where capturing portraits of the chimpanzees seems to be easier than anywhere else. Although it is formally known as Front Room 4, the staff often refer to one of the chimpanzees’ favorite locations as “The Portrait Studio” (1, 2, 3, 4). It’s popularity is likely due to the wide bench that is perfectly situated for looking down the hallway into the bustling kitchen and foyer. From the same vantage, they also can see out the window towards the garden, driveway, hay barn, neighboring cattle pasture, and even across the sanctuary to the opposite ridgeline. It’s a dream come true for nosy chimpanzees, but we caregivers appreciate the space for a different reason; the north-facing window bathes the chimpanzees in soft lighting that is well-suited for portraits.

When Burrito sat in that beam of diffuse light a couple of days ago, as he often does, I decided to snap a bunch of photos and then immediately forgot about them. Today, as I began to formulate a direction for today’s blog post, I rediscovered the series on my camera’s memory card. I then tinkered with the photographs in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom, a program commonly used for organizing and manipulating images. Of all the edits I made, I realized that I liked the way Burrito looked without any color. Black-and-white suits Bubba well.

A century ago, most photography was monochrome (gray or sepia) by default. Now, omitting or removing the hue from an image is something photographers and filmmakers purposefully do in order to create a certain aesthetic. As far as our work at CSNW is concerned, I think such a practice has merit. By taking color out of the equation, I feel more attuned to how light flows into the chimpanzees’ home, across the imposing barriers that separate us from them, and onto their facial features. It showcases the depth of their physical space and reminds me that their world, which I can only explore in a superficial manner, has a similar profundity. Furthermore, anatomical structures like hairs, wrinkles, muscles, scars and callouses give character and topography to what would otherwise be registered as a homogeneous gray body. Perhaps this medium highlights some of their more peculiar nonhuman traits while simultaneously making such differences between us and them seem more trivial. Whatever is going on in our eyes and brains, I like portraying them in this way.

Below are my favorites from the series. During processing, I tried not to dramatically alter the overall lighting, hoping instead to preserve the reality of Burrito’s location and mood. What I did tinker with, however, was the relative luminance of the various hues in the photographs, thereby changing how colors contributed to the lightness and darkness in each. Using such a mixer enabled me to create distinct portraits that were taken only seconds apart. For perspective, you can look at the print on the wooden toy block in Burrito’s hand (which is actually dark green, but appears different in each edit). I think that each has its own tone, and perhaps tells a different story. I’ll let you all be the judges.