A couple of days ago, there was fight in the chimp house that resulted in a significant injury to one of Negra’s toes. We are monitoring it to determine if intervention will be necessary, and she’s on antibiotics and pain relief.

You’d never know that she had the injury unless you actually saw it, though – Negra’s behavior is no different than normal and she was showing no signs of being in pain, even before we started her on the pain relief.

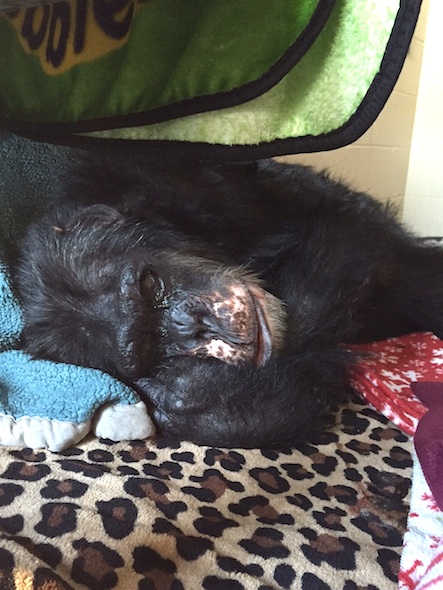

I’m just going to throw some photos of Negra in here. They aren’t from today, but they do show what Negra’s behavior is generally like:

She is getting some extra attention from the other chimpanzees because any injury is of interest to the group, with other chimps always wanting to inspect and groom wounds.

Chimpanzees can be really intense. We’ve shared information about conflicts and injuries before, and I’ve linked to a few blog posts on this topic at the end of this one, in case you are interested in further contemplation on fighting and making up as a chimpanzee. And there was this story about a conflict that resulted in one of Jody’s toes being bitten off (don’t worry – there are no gory photos in the post).

You may or may not have noticed that a few of the chimpanzees at Chimpanzee Sanctuary Northwest are missing parts of ears, fingers, and toes. Most of these injuries occurred before the chimpanzees came to the sanctuary, though some have been from conflicts that have taken place in their sanctuary home.

I accept that chimpanzees can be extremely violent. I respect that serious conflict is part of their natural behavior in social groups. That doesn’t always mean that I can just shrug off conflicts and injuries. It can be difficult to process the many facets of chimpanzees and to know that sometimes one chimpanzee who I care deeply about will hurt another chimpanzee who I care deeply about and that this will happen when I am the one responsible for the health and well being of all of the chimps here.

Maybe this is a little heavy of a blog topic.

It got me thinking about human relationships too. I often find myself explaining minor chimpanzee conflicts, which may seem like a major conflict if you’re not familiar with chimpanzees, as equivalent to a heated human verbal argument. I wonder, though, if that’s not a good comparison. After all, humans are also incredibly violent to one another.

Let’s face it, being a social primate is not that easy. We gain a lot with our social relationships, but we still have competing interests that have to be worked out one way or another; and then sometimes we’re just in a bad mood.

A recent non-invasive study of a wild population of chimpanzees was just published that found an increase in the hormone oxytocin during conflicts. Oxytocin, sometimes referred to as the “love hormone,” is perhaps most known for studies that have shown surges of the chemical in human and other animal mothers when they are with their newborns, and it’s thought to intensify the mother-infant bond. Clearly, the full extent of what oxytocin does and when it is produced is expanding. The theory put forth in this article and others about the increase of oxytocin during conflicts is that it bonds chimpanzees to their group and against a common adversary.

Perhaps the oxytocin-surge aids in the post-conflict bonding that happens with chimpanzees as well. Reconciliation is at least as important as the conflicts themselves in chimpanzees – they generally come together within minutes of a conflict ending in pairs or groups and inspect each other and groom.

Perhaps the immediate reconciliation aspect of fighting is the lesson that humans really could take from chimpanzees.

As I said above, we’ve covered the topics of aggression, conflict, violence, and reconciliation of chimpanzees in other posts before. Here are a few past blog posts if you are interested in more perspectives on these topics:

The True Nature of Chimpanzees